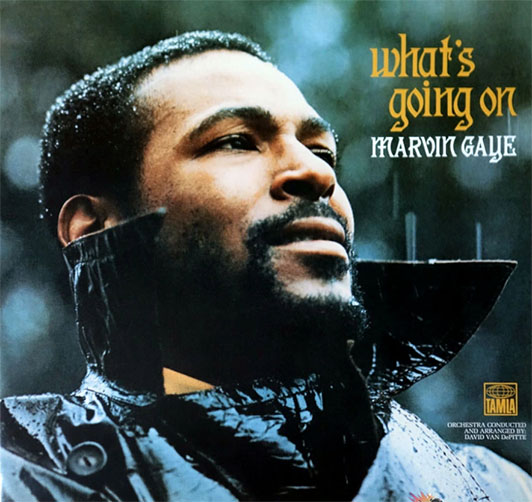

“Picket lines and picket signs

Don’t punish me with brutality

Come on talk to me

So you can see

What’s going on…”

I appreciate that my childhood spanned the 60s, 70s, and 80s. Mom and Dad passed their love of music along to me. As a kid, songs like “Sweet Caroline,” “Turn, Turn, Turn,” “Son of a Preacher Man,” and “Mama Told Me (Not to Come)” filled the airwaves. Dad’s 8-track tape case was magical with everything from the Beatles to Charley Pride.

One song I loved was Marvin Gaye’s 1971 hit “What’s Going On.” It was quite a change from his Motown days of “How Sweet it Is (To Be Loved by You),” and “Ain’t No Mountain (High Enough),” his amazing duet with Tammy Terrell. As a 7-year-old kid, I didn’t understand what the song was about. But you couldn’t grow up in those days without hearing about body counts, riots and protests on the evening news.

It’s not surprising so many songs from that era dealt with Vietnam, the antiwar protests and the civil rights movement, but none had the reach of “What’s Going On.” It was conceived by the Four Tops’ Obie Benson after he witnessed police attacking demonstrators during a 1969 antiwar protest in Berkeley, California. His friend, Al Cleveland – best known for writing Smokey Robinson’s “I Second That Emotion” – composed the first draft based on their conversations. When the rest of the Four Tops turned the song down because it was a protest song, Benson told them, “No man, it’s a love song, about love and understanding. I’m not protesting, I want to know what’s going on.” He then approached Gaye, who revised the song that would come to be ranked No. 4 of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time” by Rolling Stone Magazine.

The song’s meaning really hit me about four years ago. My best friend Eddie and I both had sons turning 16 and getting their driver’s licenses. We were excited to see our boys maturing into the men we hoped they would be, and to have bought them their first cars. I told Brooks if he was ever pulled over to be respectful. Eddie had to have “The Talk” with Kamron. Both are great kids; smart, athletic and well-liked. The one big difference: Brooks is white and Kamron is African American. All you have to do is read the newspaper or turn on the TV to see we face a lot of the same problems today.

I wonder what our world would look like if we took the time to talk to people outside our self-made circles. I’ve been fortunate to learn so much from friends like Eddie. There was also Kamal and Hamida, our neighbors when we first moved to Oklahoma City. A former co-worker, Kevin, opened my eyes to the diversity within the African American community. The more I learned, the more I changed. And the more I change, the more I learn I still have so far to go.

St. Luke’s serves more than 600 people on our 30-something Meals on Wheels routes, and we laugh at how many of them we think of as our “favorites.” For me, my absolute favorite route to deliver is Route 7, our northeast Oklahoma City route. I am struck by how much the neighborhoods look like my own, and how genuinely warm and friendly everyone is. As I type this, my face hurts from smiling when I think about people like Sister Christian, who used to serve mobile meals at her own church. Or Robert, who deals with multiple health and mobility issues, yet is so quick to laugh. These days I don’t get to deliver Route 7 often and I miss the people terribly. They’ve gone from being clients I liked to serve to people I love to see.

Seeing is what it’s all about. We seek to share God’s love and bring hope to the world; to see people as God sees them. But we have to use our own eyes. It’s only when we talk to one another that we can begin to see what’s going on.

Chris Lambert, Director of Meals on Wheels Oklahoma City